No sooner had Hugh Blaker announced his discovery of the ‘Earlier Mona Lisa’, than Paul Konody, the internationally respected art expert and critic, wrote an impassioned article about it in The New York Times on February 15, 1914:

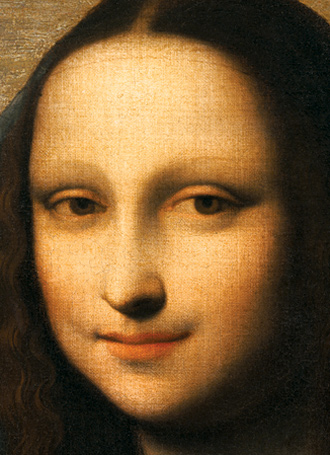

“… the features are more delicate, and, let it be boldly stated, far more pleasing and beautiful than in the Louvre version.”

It goes without saying that the Louvre ‘Mona Lisa’ attracts millions of loyal fans each year. Many see beauty in it, some do not. A notable character in the latter category was Bernard Berenson, who was not only a great art critic and dealer in his own right, but also a universally respected collector and connoisseur. For most of the first half of the 20th Century, through his expertise and attributions, he helped to create the market in Old Master paintings.

Regarding the ‘Joconde’ in Paris, he said: “What I really saw in the figure of Mona Lisa was the estranging image of woman beyond the reach of my sympathy or the ken of my interest… watchful, sly, secure, with a smile of anticipated satisfaction and a pervading air of hostile superiority.” Berenson furthermore felt that the beauty of the Louvre ‘Mona Lisa’ had been sacrificed to technique. No one has said this of the far more fresh and lively ‘Earlier Mona Lisa’.

At first glimpse, one of the most striking features of the ‘Earlier Mona Lisa’ is the critical flash of highlighting on the head, upper chest and hands. The artist wants the attention of the viewer to focus primarily on the young woman. To achieve his correct lighting objective, it would seem that Leonardo’s own instructions are being followed:

“Above all ensure that your painted figures are broadly lit from above, that is to say, whenever you are portraying any living thing.” Leonardo da Vinci, Treatise On Painting

In addition, the background in this case was not that relevant, a reason perhaps why it was left unfinished. This background was most likely not the work of the master, but that of a less talented painter.

In 1922, when the earlier version was shown to most of the well-known Italian art experts and connoisseurs of the time, the reception was universally positive, and almost without exception enthusiastic about the magical beauty of the portrait.

Unlike some of the supposition that often surrounds her counterpart in the Louvre, no hidden or even sinister agenda is anywhere to be found. In this face, Lisa is the epitome of loyalty: the faithful wife – “ … mulier ingenua”- as she is subsequently referred by her loving husband in his will.

“Do you not see that, among human beauties, it is a very beautiful face and not rich ornaments that stops passers-by? … Do you not see beautiful young people diminish their excellence with excessive ornamentation?” Leonardo da Vinci, Treatise On Painting

In this portrait, the subject comes across as not only a beautiful young woman, but also a lovable, innocent and sympathetic creature. Reserved, demure, she maintains her dignified poise and looks straight into the eye of the viewer. She is elegantly dressed in the fashion of the day, and unadorned by jewelry. It is as if the artist wanted nothing to distract attention from her face, and her face is the epitome of Renaissance masterwork representing female beauty at that time.

In fact, her gaze is mesmerizing and yet shyly seductive. Here, there is only a trace of a smile, a polite acknowledgement of one’s presence. In an Apollo Magazine article, July 1956, the respected art expert, writer and illustrator A.C. Chappelow also writes that “ … the face is superbly painted, and the hands more neatly defined than those in the Louvre painting.”

Chappelow makes a direct comparison between the earlier version, known at that time as the ‘Isleworth’ painting, and the Louvre ‘La Joconde’. He considers the ‘Earlier Mona Lisa’ as “ … a truly beautiful picture contemporaneous with that in the Louvre.” He refers to the Rome experts, cited earlier in this volume, as having considered it [the ‘Isleworth’] the more beautiful of the two, and goes on to describe how the Louvre work “ … depicts an older woman of a worldly type, whereas the ‘Isleworth Mona’ shows a younger woman.” Chappelow also refers to “ … Raphael’s sketch, also in the Louvre, clearly shows a column each side, but the Louvre painting has no columns.” He opines that the ‘Isleworth’ version was begun first, around 1501-02, “ … whilst the better-known version of an older woman was painted some years later.” At the conclusion, Chappelow enthuses “ … truly a fascinating and beautiful work of art.”

Once the artist has established the critical direction from where the light is coming, he meticulously follows his own exacting standards of portrayal. This painting, suffused with its organic tonalities, is particularly notable for the face, the bust and the hands; strongly highlighted against the subdued background.

DRAPERY

From Leonardo’s early years as an apprentice of Verrocchio, his elaborate drapery studies painted on canvas and dating from the early 1470s will attest to the great significance he attached to the importance of accurately rendering clothing. Examples of these monochromatic paintings are in the Louvre and the Uffizi.

The artist here allows no jewelry or other adornment to distract from Lisa’s exposed skin and his ability to sublimely portray it. Leonardo writes of clothing: “ … and the folds should be accommodated to the nature of the cloths, transparent or opaque …” One can almost sense the artist’s hand following the dying golden rays catching the folds on her sleeves and left shoulder: barely enough to identify the refinement, without over-emphasis. These superb highlights serve to portray the rich texture of the fabric – she was after all the wife of one of the wealthiest cloth merchants of Florence at that time – and also to dramatically introduce those magnificent hands.

THE HANDS

To many connoisseurs, her hands are almost as important as her face. Antonina Vallentin, referring to the Louvre ‘Mona Lisa’ writes of: “ … the sensuous restfulness of her hands … ” as the right hand gently rests on her left wrist, a traditional symbol of modesty. This opinion could also be applied to the ‘Earlier Mona Lisa’. The slender and uniquely executed fingers act as a kind of counterpoint to the innocence of her face. There are no wrinkles, blemishes or ugly knuckles to detract from the smooth skin, and the finely trimmed nails. Here, the artist has brought into play all his masterful techniques of light and shadow. All experts having seen the painting, have remarked on the incredible quality and beauty of the hands.

THE BUST AND THE NECK

In terms of the sheer area of this painting, the artist spares nothing. Unadorned bare flesh, bathed in light, cannot but catch our attention. Lisa’s own youthful vigour is accentuated by the shaft of light on her neck. This is an almost identical treatment to Leonardo’s earlier ‘La Belle Ferronnière’: the main difference here being the contrast between the sedate posture of the lady of the court of Milan, and the taut expectancy of the Florentine. Another comparison of course is with the Louvre ‘Mona Lisa’, but the lighting is not as strong in the Paris version, and the contoured edge of the neck-line in that portrait betrays a somewhat older woman.

The neck of the young woman in the earlier version offers an elegant femininity. The soft gradients and gentle indentations of the delightful shape are comparable, though less elongated, than those forms Leonardo styled with such genius for the ‘Lady with an Ermine’ and ‘La Bella Principessa’.

Because the young woman is angled away from the viewer, her head and right shoulder tilt slightly forward, causing the sinews to tighten the line of the neck. By comparison, the subject of the Louvre version is angled more towards the viewer, allowing the neck to be more relaxed, and displaying less muscular tension.

Furthermore, the angle of the neck, in highlight, artistically balances the subtle line of the cleavage. The loose hair falling gently on her chest is beautifully rendered, yet there is no hint of immodesty anywhere.

THE EYES

The eyes of the subject are nothing less than magnificent; perfectly rendered in every detail. The shadowing at the outer edges elongates this feature, and the shadowing on the upper side of her nose confirms the direction of the light source. A hint of the eyelashes, so fine and elegant though now very faint, are rendered as if more could never have been there. These eyelashes, alas, have almost disappeared with the eternal march of time. They were already so delicate when first outlined, but the artist could hardly have envisioned that such fragility could all but completely fade away in 500 years.

As with the loose hair falling on her bare chest, the thin veil, and the central parting of her hair, one suspects that plucked eyebrows were very much in vogue at that time. Similarly to the Louvre ‘Mona Lisa’, the eyebrows and even eyelashes are difficult to see or no longer visible. At the beginning of the 20th Century, the discussion about the eyebrows and eyelashes was very active among scholars and writers. Eugene Muntz, a Leonardo biographer, reported that “Every eyelash was carefully studied…” and that though now lacking “ … faint traces of them and the shadow they cast on the cheek are still discernible.” Salomon Reinach, Louis Zangwill and André-Charles Coppier all pointed-out another possibility; that society ladies during the Renaissance were known to have plucked their eyebrows and eyelashes with a steel tweezers called a pelatoio. The Russian writer Dmitri Merejkowski also remarked on the use of this instrument at that time.

However, Pascal Cotte, in an ultra-high resolution photographic close-up of the Louvre ‘Mona Lisa’ recently found evidence of eyebrows: both versions of the Mona Lisa likely originally had eyelashes and eyebrows. Under intense magnification, faint traces of what Vasari described as being in full bloom, can still be recognised.

THE NOSE

The nose is highlighted almost as a natural extension of her forehead. The light curves sensually around the shadowed recesses of her eyes, and falls gently as if caressing the surface of her perfect nose, finally accentuating those delicate nostrils.

THE LIPS

Everything about this painting exudes an air of serenity and relaxation. The beautiful mouth is simply rendered. Even the reddish hue of the lips has an earth tone that blends seamlessly into the surrounding natural skin colour. The lips touch gently at the front of her mouth, and then only barely: the rest of her mouth is very slightly if perceptibly open. It is as if her lips just rest together.

It is at the edges of her mouth that the artist employs his ‘sfumato’ technique to give the illusion of a slight smile.

The facial muscles again are totally relaxed. There are no laugh-lines near the eyes, nor signs of any wrinkle due to laughter.

THE FACE

In terms of pure magic, the face is the sum of its parts. Every item inspected separately is exquisite. The rendering is flawless. The face overpowers our first gaze and overwhelms our reflections on possible comparisons and impressions. The brilliance of eyes, mouth, lips, cheeks, balanced so magnificently on the delicate and fragile neck, leave us breathless. The aura of shining light pierces the inner soul of the viewer.

The subject is blessed with wonderful genes: she is beautiful and gentle. In the artist’s eyes she has almost near-perfect features. For him too, she must have had an extraordinary natural personality. Professor Carlo Pedretti argues that the ‘Earlier Mona Lisa’ “[displays] a most beautiful face charaterised by a countenance that is strikingly younger than that in the Louvre painting.”