When this subject arises, there are great differences of opinion among Mona Lisa ‘aficionados’. Almost since the time that Vasari had published his identification of a certain Leonardo portrait as being of Lisa, the wife of Francesco del Giocondo, historians, scholars and writers realized that there were inconsistencies between his description and the painting in the Louvre, and as a result, they have been jousting about its origin, authorship, provenance, and whether there might have been another, original version by the great master.

The translation and distribution in the early 20th Century of The Travel journal of Antonio de Beatis created a whole new dialogue about the identity of the subject. The Louvre version, ‘La Joconde’, was no longer simply Mona Lisa del Giocondo, but perhaps instead somebody else, and commissioned by a different personality, the ‘Magnificent’ Giuliano de Medici, who, on paper at least, had greater resources and prestige than the Florentine merchant. More fuel was added to the fire when, in his 1914 article La “Joconde” est-elle le portrait de “Mona Lisa”?, Andre-Charles Coppier unleashed an avalanche of doubt. Many art historians were quick to link that article with the earlier de Beatis history, leading to a wild scramble to come up with suggestions as to whose portrait the fickle Giuliano would have commissioned. Since it is known that, in January 1515, Giuliano, for purely political purposes, was married to the 16-year-old Philiberta of Savoy, the subject was simply assumed to have been a mistress. There is a sense that every woman of note who may have been in Rome between 1513 and 1515, and a few others besides, was his mistress, or at least, favourite to be proposed as a Mona Lisa replacement.

Today, most experts are divided into two camps. Some of those who support the Vasari history, i.e. that the ‘Mona Lisa’ is indeed Lisa del Giocondo, do so while believing that it is yet the painting (inconsistently) connected to Giuliano de Medici. At variance, many contemporary experts have confirmed that the glazing and painting techniques in the Louvre version date specifically from Leonardo’s later period, and definitely after 1508. That being the case, there are those who now dismiss Vasari and the del Giocondos, and, as a consequence, numerous other contenders have been proposed over the last one hundred years or so. Regarding the latter there are many doubters.

Charles Nicholl wryly commented: “Their proponents seek to solve a mystery, but one must first ask ‘Is there really a mystery to solve?’”

There have been all kinds of proposals as to the woman’s identity, from the remotely possible to the preposterous.

Sigmund Freud insists, without any evidence, that the Louvre masterpiece represents the artist’s mother, and focuses specifically on a theoretical connection between the smile of the ‘Mona Lisa’ and the imaginary smile of Leonardo’s own mother. In a sense, what else could have been expected from Freud? He was certainly no art critic. Philosophy professor George Boas explains: “ … An artist, according to Freud, is a man whose sexual frustrations are released symbolically in pictures or statues or other works of art. Appetites that could never pass the Censor if expressed in their true nature, are permitted to appear in disguise.

As is well known, according to this theory the fundamental appetite of the human male is his love for his mother, known as the Oedipus Complex. Since incest in most Occidental society is not encouraged, the Oedipus Complex can only be released through art, and hence a Freudian critic will be likely to see in a picture a symbol of the artist’s passion for his mother. Here, it will be observed, the critic assumes that the artist is not communicating something to the observer – he is really concealing something from the observer – but unconsciously expressing something of himself.”

Others have submitted that the Louvre version is actually Leonardo’s own self-portrait, and that there are sufficient facial similarities to justify this. In a recent book – Leonardo’s Hidden Face, 2007 – the lead author, Lillian Schwartz, proposes that a reverse image of Leonardo’s well-known ‘Portrait of an Old Man’, done in red chalk, now in the Royal Library, Turin, coupled with a split image of the Louvre ‘La Joconde’, demonstrates that the subject is Leonardo himself. Unfortunately the computerised analysis used for this test remains inconclusive. In addition, the Leonardo drawing in question has never been proven to be a selfportrait. Leonardo himself, with characteristic dry wit in his Treatise On Painting warns against this:

“… for you might be mistaken and choose faces which resemble your own; … and you would make ugly faces as many painters do, with figures that often resemble the master …”

Still other commentators believe the Louvre portrait to be a fictionalisation of Leonardo’s ideal woman, and not of a real person at all. This theory dismisses all the existing history and documentation, and remains without any strong evidence supporting it.

Perhaps, not one of these ideas merits serious consideration. The fact is, however, that there are other contenders to be the woman of the Louvre version, and this is largely due to a misinterpretation of the 1517 commentary of Antonio de Beatis.

‘ … one of a certain Florentine woman, done from life, at the instance of the late Magnificent Giuliano de’ Medici…’

Looming large in all this is the descriptive extract above from the de Beatis journal, the quotation that has given rise to so much speculation. These lines will recur time and time again in the evaluation of possible candidates. Simply put, if the lady proposed cannot meet the criteria, she must be eliminated from contention. There has never been any serious doubt about the veracity of de Beatis’s diary, which has long been established as a most dependable source.

Here are the women most frequently proposed:

COSTANZA D’AVALOS DE BALZO (1460 – 1541), DUCHESS OF FRANCAVILLA

Her name surfaces as the possible subject of the Louvre ‘Gioconda’ in 1929, when Professor Adolfo Venturi proposed the idea. In various publications and articles, including Giornale d’Italia, Il Mattino, and Storia dell’Arte Italiana, Venturi makes a few points, which have also been supported by a few others, including Henry Pulitzer. However, the whole theory is flimsy at best.

- Venturi opines that the woman of the Louvre portrait is wearing a widow’s veil. Costanza d’Avalos was a widow, and therefore this was a reason for her to be considered. This is truly grasping at straws. Costanza was married in 1477, and was already a widow by the turn of the century. Giuliano de Medici would probably not have commissioned Leonardo to paint anything until about 1513 at the earliest, when Leonardo arrived in Rome at his invitation. That seems like an inordinate amount of time for a widow’s veil to be worn. Furthermore, the thin veil that Leonardo painted in both versions of Mona Lisa is likely not a widow’s veil.

- Venturi goes on to suggest that Costanza was reputed to have been of cheerful and pleasant demeanour, though it is far from certain how this could ever be verified. However, it was that which led to the nickname ‘Gioconda’ being applied to her. Even so, that is an extremely tenuous link to the Louvre painting, and as has been mentioned earlier, this appellation had already been in use since the 13th Century.

- Venturi continues with a reference to a group of verses (c.1510) by the poet Enea Irpino da Parma, in which, infatuated with Costanza, he (the poet) refers to a portrait of her by Leonardo. It is described in loving detail, and extravagantly eulogises the greatness of “Vincio”, and the greater worth of Costanza, with her “ … noble and sublime intellect, beautiful eyes …” She was also a military heroine of a sort, having successfully defended Ischia and her castle home there against the French in 1501.

However, there is no evidence at all that she knew Giuliano, or was ever a mistress of his or anyone else, or that she ever posed for Leonardo, or that he, in turn, had the time or opportunity to paint her. When, or if, Leonardo was commissioned by Giuliano to paint the portrait now in the Louvre, it must have occurred after they were both in Rome at the same time, i.e. between 1513 and 1515. By then, the widow Costanza, born in

1460 and already 19 years older than Giuliano, would have been in her mid-fifties.

It is known that Giuliano’s attentions, when he had the energy, were directed at much younger women. As Professor Josephine Rogers Mariotti relates, in August 1514 Giuliano locked himself in the Medici palace in Florence for three days with different women. This would not have been a good prognosis for him to request a portrait of Costanza.

There was another Costanza d’Avalos around that time, but she too was not the subject of the ‘Gioconda’. Married in 1517 to Alfonso Piccolomini, she was never reported to have met Giuliano, or even to have visited Rome. In any event, she would have been much too young for the date of Leonardo’s later portrait. She was a cousin of Vittoria Colonna, and became Duchess of Amalfi. She died in 1560.

Perhaps what disqualifies the Duchess of Francavilla is that she was Neapolitan. Both Cardinal Luigi and Antonio de Beatis had strong connections to Naples, and would therefore have easily recognized Costanza. Yet when they were shown the painting, it did not elicit any particular reaction from either of them.

Finally, Leonardo’s own words, faithfully transcribed by de Beatis, specify that the subject is “… a certain Florentine woman … ”. Costanza d’Avalos is thus unlikely to be the subject of the Louvre portrait.

ISABELLA GUALANDA

The establishment of the identity of the Louvre ‘Gioconda’ took another twist with the inscription of this Isabella’s name as little more than a passing reference in The Travel Journal of Antonio de Beatis. The visit to Leonardo at Cloux (now Clos-Luc้), by the Cardinal of Aragon and de Beatis, his diarist, chaplain, colleague and amanuensis.

On that day, October 10, 1517, one of the paintings shown to them by Leonardo is described as “ … one of a certain Florentine woman, painted from life, at the instance of the late Magnificent Giuliano de Medici.” These words constantly recur, and cannot be overemphasised. The next day, October 11, they are at Blois nearby, where they see:

“… vi era a[n]cho u[n] qu[a]t[r]o doue e pi[n]tata ad oglio una certa Sig[no]ra de lombardia di naturale assai bella: ma al mio iuditio no[n] ta[n]to come la s[ignor]a gualanda:”

“… an oil painting of a certain Lady of Lombardy, done from life, a beautiful woman indeed: but in my opinion less so than Signora Gualanda:…”

In the margin of the manuscript, de Beatis later clarifies her identity as ‘Signora Isabella Gualanda’.

This is really the first reference we see of Isabella Gualanda. She was actually born in Naples in 1491. Her father, Ranieri Gualandi, originally from Pisa, was a general courtier to Alfonso of Aragon, Duke of Calabria. Some historians link her father’s Tuscan origin as sufficient to qualify her as Leonardo’s Florentine woman, but this is stretching what can be believed.

Regardless, some Leonardo experts came to the conclusion that de Beatis implied that Signora Gualanda was the Florentine woman they had seen the day before, and that therefore she was the ‘Gioconda’ (or ‘La Joconde’) of the Louvre. However, careful reading of the famous diary, and an understanding of its author, clearly refutes this theory. If the Florentine woman was Gualanda, then de Beatis, who had a penchant for name-dropping, would probably have said so the previous day. Even afterward, he never mentions any connection.

Isabella’s mother, Bianca, was a cousin of Cecilia Gallerani, subject of the ‘Lady with an Ermine’, the superb portrait that Leonardo executed c.1489-1490. Sadly, Isabella was orphaned as a baby, and from 1492 she was brought up under the protection of the Aragonese court in Naples. By 1514, then widowed and a mother, she was possibly in Rome, and connected to the social circle of Vittoria Colonna, that also included Costanza d’Avalos, the Duchess of Francavilla, and other intellectual ‘emigres’ from Naples. There are reports extolling her wit and beauty. Nonetheless, there is no evidence that she had anything to do with Giuliano de Medici.

Luigi of Aragon, the Cardinal, would certainly have known of her from the court at Naples.

De Beatis himself, like Luigi, also had an eye for beautiful women – his diary is littered with remarks about and comparisons between the beauty of women they encountered while touring around Europe. Without the de Beatis comment, she might have disappeared unknown into history. Interestingly, there are no known portraits of Isabella Gualanda to serve as a basis for comparison.

The oil painting of the Lady of Lombardy that they saw at Blois is considered to be the ‘Portrait of a Lady of the Court of Milan’, taken as booty by Louis XII from Ludovico Sforza, and now in the Louvre.

Further examination of de Beatis’s remarks reveals additional clues “ … una di certa donna fiorentina …” – “ … a certain Florentine woman … ” In these words Leonardo implies anonymity; his instinct was clear that his Neapolitan guests would not know the middleclass housewife from Florence, and that her name was really not relevant. His appellation of “ … donna … ” categorises her as an ordinary woman, not nobility. The guests in turn, do not display the slightest recognition of her.

When, the following day, de Beatis refers to “ … Signora Gualanda … ”, he is not only identifying someone he recognizes, but the use of “ … Signora … ” instead of “ … donna …” places Gualanda in a higher social category. The two women are not one and the same. Based on this evidence, Isabella Gualanda, therefore, would not be the subject of the Louvre portrait.

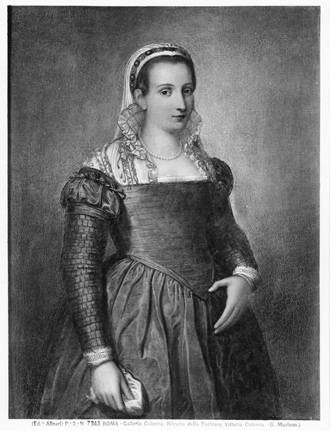

VITTORIA COLONNA (1490 – 1547)

Portrait of Vittoria Colonna, by Girolamo Muziano.

The talented and famous Vittoria Colonna was never considered to have been either a mistress or favourite of Giuliano de Medici, or a subject for the ‘Gioconda’. This brief passage is included because she was so well connected to some of the other contenders, such as Costanza d’Avalos and Isabella Gualanda.

Born in Marino, near Rome, she was Costanza’s niece by marriage, and for some years of her childhood was reared and protected by the duchess. Vittoria was loyal to her philandering husband, though as a widow later in life, she became a great friend of Michelangelo, and the object of his intellectual passion. Michelangelo was heartbroken when she died in 1547.

Vittoria was a published poet, and was reputed to have hosted for some time a society ‘Salon’ in Rome. She was also recognized as a woman of high virtue and nobility; traits that contrasted with some of the corruption and treachery for which the Italian Renaissance is known. She lived most of her life on the island of Ischia and on estates around Naples. Details of when she was in Rome, how long she stayed, and whether her ‘Salon’ was active there, are sketchy. There is really no hard evidence linking her, Costanza d’Avalos or Isabella Gualanda to Rome during the brief period when Leonardo and Giuliano were there together.

Furthermore, Vittoria was not from Florence, and due to this point alone she would not qualify to be the subject of the Louvre portrait.

ISABELLA OF ARAGON, DUCHESS OF MILAN (1470 – 1524)

Partially pigmented bust of Isabella of Aragon, by Francesco Laurana.

This Isabella comes across as one of the more tragic figures of this period. Disappointment and doomed expectations dogged most of her entire adult life.

She was married to her first cousin, Gian Galeazzo II Maria Sforza, erstwhile Duke of Milan. But her weak and ineffectual husband was usurped by Ludovico ‘Il Moro’, and died soon afterwards. She outlived three of her four children. After the collapse of the Sforza dynasty she was permitted lands and title in Bari, where she spent her remaining 25 years in semi-seclusion.

Isabella of Aragon was first suggested as the ‘Gioconda’ of the Louvre in 1979 by Robert Payne, and later, in 2003 by Maike Vogt-Luerssen. The connection has nothing to do with Giuliano de Medici, and the theory pre-supposes that Leonardo painted her portrait in the 1490s, during his first Milanese period. However, the painting has been officially dated later.

There is a pattern on the dress in a certain portrait reputed to be of Isabella – but there is no certainty that the portrait is of Isabella; no record of Leonardo having painted her portrait; and the suggestion that a dress pattern ties that woman to the ‘Gioconda’ of the Louvre is extremely flimsy. It should be remarked that the famous cloverleaf pattern on the blouses of both original versions of Mona Lisa bears a resemblance to a design Leonardo had executed on a ceiling of Ludovico Sforza’s palace some years earlier.

Cardinal Luigi of Aragon was actually her cousin. He would easily have recognized her in Leonardo’s portrait, and that would certainly have been noted in the diary of de Beatis.

There is one further piece of damning evidence, and this time it comes from Antonio de Beatis himself. While touring Blois on October 12, 1517, with Cardinal Luigi, they visit some stables where King Francois I maintained his horses. There they see one of the breed belonging to “ … my most illustrious lady, the Duchess of Milan.” After 1500, Isabella of Aragon was permitted to keep the courtesy title of Duchess of Milan. De Beatis was Canon of Molfetta, which is only a short distance (about 35 km) up the coast from Bari. De Beatis’s comment clearly implies that he not only knows Isabella, but acknowledges her authority, and may well have served at her court.

She was not recognized in Leonardo’s portrait, and in any event, was Neapolitan, not Florentine. She, also, is likely not the subject of the Louvre portrait.

PHILIBERTA OF SAVOY, DUCHESS OF NEMOURS (1498 – 1524)

Bronze medallion of Philliberta of Savoy, based on the original c. 1516.

She was the young princess that the consumptive Giuliano de Medici reluctantly married in 1515, in order to assist his brother, Pope Leo X, in cementing a new alliance with the French.

Philiberta was the younger sister, by 22 years, of Madame d’Angouleme, the mother of Francis I: so in spite of her age, she was, in effect, Francis’ aunt. Alas, she is reported to have been “ … a thin girl with a pale, pinched face, and almost a hunchback … ”

She does not resemble in any way the subject of the Louvre ‘Mona Lisa’. Philiberta, as Giuliano’s wife, would have been easily recognised by Cardinal Luigi. In addition, as Giuliano’s widow, she likely would have inherited the portrait directly, if it was of her. Finally, she was most definitely not from Florence, and is not the subject of the Louvre portrait.

ISABELLA D’ESTE, MARCHIONESS OF MANTUA (1474 – 1539)

Portrait of Isabella d’Este, by Leonardo da Vinci. The work dates from c. 1499-1500, executed during Leonardo’s brief visit to Mantua after fleeing Milan. In this portrait Isabella is about 26 years old.

Isabella d’Este was unquestionably one of the leading figures of the Italian Renaissance, and for the most part the few comments about her here really do an injustice to her many accomplishments and dynamic personality. Her name appears from time to time as a likely candidate to be the woman in the Louvre masterpiece, and it is entirely possible that she met Giuliano de Medici, even while he was in exile prior to 1512. But under no circumstances was she ever his mistress, or considered a favourite, and there is no mention of Giuliano ever having requested a portrait of her. She had her own frustrating dealings with Leonardo, expressed in considerable correspondence.

After he fled from Milan in 1499, Leonardo and his small entourage were given hospitality by Isabella at Mantua. While there, Leonardo did produce two portraits of her, which Isabella describes as “ … in carbone …” and not in colours; drawings really for a promised painting. Isabella’s husband subsequently gave one of them away: the other, Leonardo took to Venice, where he showed it to Lorenzo Gusnasco of Pavia, a craftsman of superb musical instruments. This is the one believed to have survived, and is now in the Louvre.

Among her many talents, she was an avid art patron and collector. Ambitious, driven, and imperious, she was the equivalent of what is referred to today as a ‘type-A personality’. However her reputation was that she focused on what she wanted, and nagged until she got it. She not only awarded commissions to the great artists of the day; she demanded their work. As she wrote to the court poet Niccolo da Correggio, she liked to “ … have her wishes gratified on the spot.”

Paying was another matter. Word in the artistic community was that wrenching money out of Isabella was like squeezing blood from a turnip. Jacob Burckhardt writes that her treasury did not contain the funds to pay for anything, and Bruno Nardini comments that she “ … prided herself on discovering contemporary talent and collecting its works … on condition that they cost little or nothing.”

Ironically, it was traits like these that were instrumental in inhibiting the conservative Leonardo from accepting her commission for a painting of any description. Always prudent with money, he instead turned his energies to producing the Mona Lisa. As far as her candidacy to be the subject of the Louvre ‘Gioconda’ goes, there are a few more points:

• Isabella was not Florentine, having been born in Ferrara.

• She, like her sister Beatrice, and Isabella of Aragon, was an actual cousin of Cardinal Luigi. They all had the same grandfather: King Ferdinand (Ferrante) I of Naples. Luigi would easily have recognized her. It is no coincidence that towards the end of their ‘Grand Tour’ in January 1518, Cardinal Luigi, de Beatis, and the whole entourage, stayed with Isabella in Mantua for about three weeks.

She was not the subject of the portrait that Leonardo showed to Cardinal Luigi, and is therefore not the ‘Gioconda’ (‘La Joconde’) in the Louvre.

PACIFICA BRANDANO

Pacifica Brandano (the surname is spelled variously e.g. Brandani, Brandino, etc.), a heretofore unknown woman from Urbino, had a relationship of some sort with Giuliano, at least as far back as 1510 when he was still in exile and staying from time-to-time at the court of Urbino. This is known because their son, Ippolito, the only known child of Giuliano, was born in 1511. Ippolito was subsequently brought up under the aegis of his uncle, Giovanni, who became Pope Leo X. Ippolito himself later became a cardinal.

It is believed that Pacifica died shortly after giving birth to Ippolito, and very little else is known of her. Furthermore, Giuliano seems to have taken little interest in his illegitimate son. All of this speaks volumes about his relationship with Pacifica, none of it compelling enough to have had one of the greatest artists of his time paint her portrait.

In addition, Pacifica was from Urbino, not Florence. Not being Florentine seems to be the ‘coup-de-grace’ in common to all these proposed candidates. There are no known images of Pacifica to serve as a basis of comparison. She is not the subject of the Louvre portrait.

CATERINA SFORZA, COUNTESS OF FORLI (1463 – 1509)

Portrait by Lorenzo di Credi of a Lady, considered to be Caterina Sforza, “The Tiger of Forli”.

She was the illegitimate daughter of Galeazzo Maria Sforza, Duke of Milan and his mistress Lucrezia Landriani, wife of one of the Duke’s friends. Caterina was another of the colourful and strong-willed characters of the Italian Renaissance, and her action packed biography has fascinated historians for centuries. She was married three times, had countless lovers, and eight children. Her many exploits, passion, and reputed fiery temperament earned her the nickname ‘The Tiger of Forli’.

Her third husband, Giovanni de’ Medici il Popolano was actually a distant cousin of Giuliano, but there is not a shred of evidence that she ever had a ‘relationship’ with Giuliano, who, in any event, was 16 years her junior.

Her third husband, Giovanni de Medici il Popolano was actually a distant cousin of Giuliano, but there is not a shred of evidence that she ever had a relationship with Giuliano, who, in any event, was 16 years her junior. Furthermore, she was not a Florentine, the critical qualification. She died in 1509, four years before Leonardo came to Rome under Giuliano’s aegis. Caterina is therefore not the subject of the Louvre portrait.

Concluding comments

Let the critically important description by de Beatis be reviewed one more time:

‘uno di certa dona fire[n]tina facta di naturale ad instantia del quo[n]dam Magn Juliano de’ Medici…’

‘one of a certain Florentine woman, done from life, at the instance of the late Magnificent Giuliano de’ Medici…’

It does seem puzzling why so many learned scholars are second-guessing those carefully chosen words. They are clear and concise and point to the fact that:

• She is Florentine.

• She is just “ … a certain woman … ” Leonardo saw clearly that the woman in the painting was not recognized at all by Cardinal Luigi or Antonio de Beatis. She is anonymous to them; also untitled, not of nobility, and plainly just ‘middle-class’.

• “ … facta di naturale … ” – “ … done from life …”. She was a real person, who posed live for Leonardo; not a figment of his imagination. She and Leonardo would have had to have been in the same studio at the same time, at least once. As mentioned eslewhere, the hypothesis that the subject of the Louvre version, started c.1513, is in fact an age-progressed version of the same subject, done from how Lisa would have look in life at that time, as has been confirmed through forensic analysis. ‘The Regression Project’ compares the two images of Lisa; like photographs taken 12 years apart: the earlier one satisfying the Vasari description; the Louvre ‘Mona Lisa’ complying with Leonardo’s later style.

• “ … the ‘late’ Giuliano … ” Cardinal Luigi was a colleague of Pope Leo X, Giuliano’s older brother, and would certainly have known at the time of the visit to Leonardo that Giuliano had died exactly 19 months previously. At least one scholar has implied that Leonardo was deliberately coy about the woman’s identity, to protect the reputation of Giuliano. There is no reason to doubt the integrity of de Beatis, or to think that he did not faithfully transcribe the information. In any event, as for Giuliano’s reputation: he was hardly a paragon of virtue.

• Finally, there are what must likely be the key words in the phrase: “ … ad instantia … ” These words imply a commission, not in the sense of Giuliano perhaps saying to Leonardo: ‘There is a lady I know whose portrait I would like you to paint.’ Giuliano de Medici likely saw the ‘Earlier Mona Lisa’ and commissioned Leonardo to paint a version of it.

Leonardo had been carrying around the unfinished painting of Vasari’s description, and when commissioned by Giuliano to paint a version for him he created a second version, a slightly different composition on a wooden panel, and based it on the live portrait of Mona Lisa.

This being the case, then the subject was undoubtedly also Lisa. In a masterful example of scientific application, Leonardo would have ‘progressed’ the age of the woman to what she would have looked like about 11-12 years after the first portrait, and thus making the later version not only contemporary to his period with Giuliano, but utilizing newer techniques and style, such as his later glazing technique, which he had developed since leaving Florence. He takes into consideration the subsequent births and deaths she persevered, the daily struggle of life, and the toll it has taken on her appearance.

The only logical conclusion is that the Louvre version must indeed represents Lisa del Giocondo at the age of about 35 years, and its execution post-dating the ‘Earlier Mona Lisa’ by approximately 11-12 years.